Endometriosis - What is it?

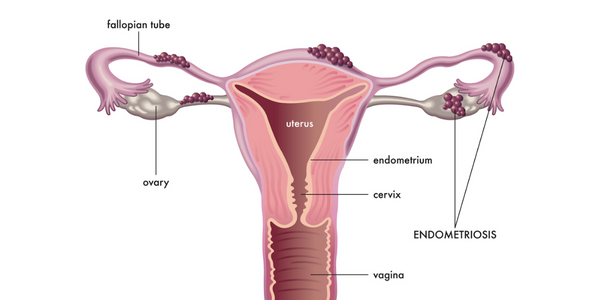

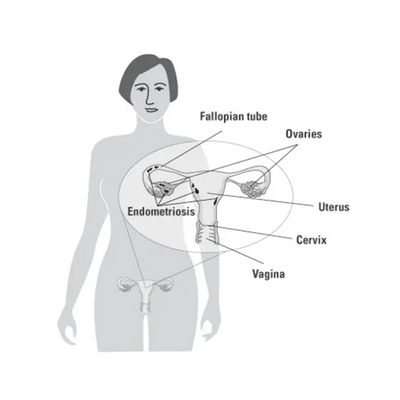

Endometriosis is a common female gynecological condition that occurs when cells from the lining of the uterus grow in other areas of the body. It is a chronic, benign (non-cancerous) inflammatory disease, defined by the existence of “ectopic” (misplaced) endometrial (uterine lining) tissue. In other words, uterine lining cells that exist outside the uterus, such as in areas of the pelvis near the uterus, the vagina, cervix, intestines, bladder, or, rarely, in more remote areas of the body. These tissues grow, thicken, breakdown, and bleed just like the endometrium inside the uterus, except because they’re outside, this cycle can cause irritation or inflammation in surrounding organs or even produce scar tissue, known as “adhesions,” that can cause organs to attach to each other.

Experts estimate that it affects at least 10% of reproductive-age women.

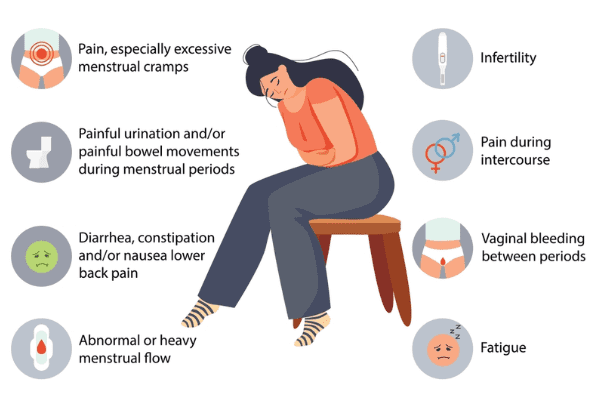

Symptoms of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is typically diagnosed between ages 25 – 35, although the condition probably begins about the time that regular menstruation begins.

What happens exactly?

Every month, hormones are produced in a woman’s ovaries that tell the cells lining the uterus to swell and get thicker. These extra cells are removed from the uterine lining each month when you get your period.

Endometriosis results if these cells (called endometrial cells) embed and grow outside the uterus. Women with endometriosis typically have these growths on the bladder, ovaries, rectum, bowel, and on the lining of the pelvic area. They can also occur in other areas of the body.

Unlike the endometrial cells found in the uterus, the tissue implants outside the uterus stay in place when you get your period. They sometimes bleed a little bit. They grow again when you get your next period.

This ongoing process can create adhesions, which are bands or sheets of scar tissue that can form around your fallopian tubes, ovaries, uterus, bladder or bowels and leads to pain and the other symptoms of endometriosis. Adhesions may cause pelvic pain, and they may reduce your fertility or make you infertile if they interfere with an egg getting into your fallopian tube, or completely block one or both tubes. They are most dangerous if they interfere with the function of your tubes and you could be at risk for a tubal pregnancy (ectopic pregnancy).

Why it happens?

The cause of endometriosis is unknown. One theory is that the endometrial cells shed when you get your period travel backwards through the fallopian tubes into the pelvis, where they implant and grow. This is called retrograde menstruation. This backward menstrual flow occurs in most women, but researchers think the immune system may be different in women with endometriosis.

Diagnosis of Endometriosis

The diagnosis of endometriosis depends very much on whether or not you are trying to conceive as well. Some women with early-stage endometriosis have little or zero pelvic pain or fertility issues. We used to diagnose these women when they had a laparoscopy to tie their tubes (there are now less invasive ways to block the tubes in women who are done with childbearing).

The ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis is still to perform a diagnostic/operative laparoscopy, an outpatient surgery performed under anesthesia where a small incision below your belly button allows us to pass a surgical telescope into your abdomen and pelvis and look for endometriosis and often destroy or cut out endometriosis if we find it. More advanced endometriosis may show up on pelvic ultrasound (a sonogram which is best performed with a transvaginal probe), but early-stage endometriosis will not show up on ultrasound. If you are trying to conceive, a hysterosalpingogram (HSG) does not ‘see’ endometriosis but looks for blocked tubes or scar tissue around the tubes, which can occur in women who have endometriosis, as well as for other reasons like past infections.

If you have just been diagnosed with endometriosis and are ready to conceive it is recommended that you see a Fertility specialist no matter what your age is, or how long you have been trying so far. Even if the endometriosis was diagnosed by laparoscopy and treated at the same time we will check out your ovarian reserve (the number of eggs left in your ovaries). Even some women in their early 20’s with endometriosis have badly reduced ovarian reserve. This can be tested by a sonogram of your ovaries looking at the size of your ovaries and number of small egg-containing follicles (Antral Follicle Count), and blood tests including FSH, Antimullerian Hormone (AMH) and the Clomid Challenge Test. You may look great on these tests but it’s good to know either way rather than try for a year then find out there’s a problem.

If you were diagnosed with endometriosis by laparoscopy your MD may have done a dye test of your tubes (chromotubation) to make sure both sides are open, as well as checking for scar tissue (adhesions) around the tubes or ovaries which can make it harder to get pregnant. If not, an X-ray dye test of your tubes (hysterosalpingogram or HSG) should be done.

Endometriosis and Infertility Treatment

Many women with endometriosis will conceive, but some will have a harder time getting pregnant. It depends on how bad the endometriosis is, and whether or not the endometriosis has caused low egg supply (diminished ovarian reserve), or caused scar tissue around your tubes or ovaries or blocked tubes. Some women get both low egg supply and tube problems.

Some women with endometriosis have no problems getting pregnant (for example a woman with 3 kids getting a laparoscopy to have her tubes tied may have a couple of spots of endometriosis inside her pelvis), and some women with endometriosis have a very hard time getting pregnant and may need more aggressive fertility treatment compared with women their age without endometriosis.